It’s crazy to love something that can’t love you back.

For me, that thing is journalism. It will never love me or save me or sustain me. It doesn’t care if I’m a reporter or an editor or if I throw in the towel and sell insurance. It doesn’t care if I do great work or get by with clickbait. But I keep coming back for more of this relationship that is defined mostly by unrequited love. Maybe you do, too.

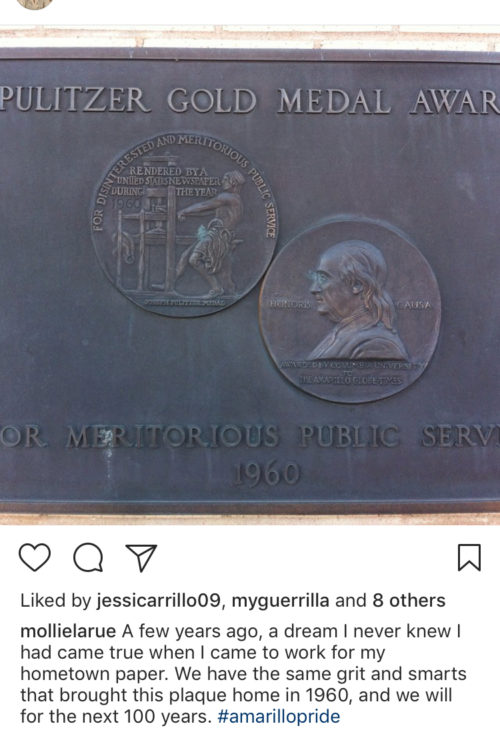

On Sunday, I was feeling reflective, looking through old Instagram photos, and saw this photo I’d taken in 2014 of a commemorative plaque given to my hometown newspaper, the Amarillo Globe-News in Texas. The paper got the plaque along with a Pulitzer in 1960 for meritorious public service after exposing widespread corruption in local government.

On the post I’d written, “A few years ago, a dream I never knew I had came true when I came to work for my hometown paper. We have the same grit and smarts that brought this plaque home in 1960, and we will for the next 100 years.”

The irony was palpable, because two days earlier, the paper had laid off its last photographer. Just as dire, there is only one full-time news reporter on staff.

About 200,000 people live in Amarillo, and the Panhandle as a whole is home to about 430,000. Now a single reporter is responsible for keeping up with every aspect of the region – crime, courts, local government, education, business, politics, and on top of that, the only nuclear arms factory in the country and a city with the largest refugee population per capita in the state.

It’s no treat attempting to negotiate the past with the present, and I know that things weren’t perfect before or during my time at the paper. But I felt proud of what we did and proud to work with the reporters whose bylines I grew up reading. Many of them could have worked anywhere but chose to stay in their hometown. For a while, I wanted to do the same.

Now I’m getting to the crux of something I’ve struggled to understand and work through since I started reporting: how the flagging newspaper industry has shaped not just the course of my jobs but my career itself.

I started reporting in 2011, and since then, I’ve worked at three newspapers – a small-town daily, the Amarillo Globe-News and The Clarion-Ledger in Mississippi. I was excited as hell for each of those opportunities, but in many ways, it felt like I was jumping from one sinking ship to another.

In Amarillo, jobs disappeared thanks to attrition, leaving reporters covering multiple beats. For instance, I was supposed to be on the education beat, but I also wound up covering crime and courts off and on the whole time I was there. An ambitious video project meant everyone was responsible for shooting and editing video with each story they wrote, meaning we had to choose topics that worked well with video and that we had way less time to write and report. Because the paper’s site had less content, our pageviews went down, which became stressful due to pageview “goals” that rose every month. On top of all that, I knew at that point that I wanted to be a full-time investigative reporter, and I was working about 20 hours off the clock each week in order to turn enterprise stories in. There simply wasn’t enough time during the week with all our other duties, and I couldn’t just not do the in-depth stories that I loved doing.

I eventually found the perfect opportunity as an investigative reporter in Mississippi. I had an incredible editor and mentor, along with a team of colleagues who inspired me every day to do my best. Within a year, Gannett laid me off.

I just searched “investigative reporter” on journalismjobs.com, which is more or less the go-to spot for openings at newspapers. Three investigative positions have been posted in the last month. It was basically the same level of opportunity when I was laid off in 2016. You and every other poor journalism schlub were looking at the exact same job listings.

I did eventually find an investigative position of sorts, but the job search was nerve-racking. I found myself in this uncomfortable position where competition was fierce for just a few positions, like some hellish American Idol where you’re singing “Careless Whisper” for just a phone interview. On one end, editors at prestige media organizations have a huge array of journalists to choose from. I saw those positions go to reporters who had worked at places like Vice and the New York Times.

On the other end, editors have incentive to find whoever they can pay the least. I was told several times that I was overqualified for positions, even though they were in larger markets, and then I’d see them go to people who had just graduated from college. I felt like at 29 years old, I had somehow peaked. I was too old and experienced to get a job that was one rung higher, so I’d never get a job that was two rungs higher.

I spent a lot of time wondering if the problem was me, and I spent even more time puzzling over what I’d done wrong to warrant being laid off in the first place. But in the job search, I grew increasingly tired of asking for permission to do what I love. After going on to work for an editor who found me to be a sub-par reporter and writer with equally poor ideas, I’m through with journalism being one series of compromises after another. It’s crazy to love something that can’t love you back. It’s even crazier to let that thing hurt you.

So, here we are. It’s 2018, and there are limited opportunities for reporters. News orgs, no matter their size, are struggling to cover everything they can while holding the powerful to account. At the same time, even though Americans have access to all the knowledge on earth at their fingertips, many of us choose news sources that are misleading, inaccurate, dishonest or the work of conspiracy theorists. The president thinks of the media as the “opposition party.” People wear shirts that joke about lynching reporters.

We can’t give up on journalism, but we can’t let it hurt those of us who take it on as a career, either. We have to do something, and we have to do it now.

I think non-profit models are our best chance to save the newspaper industry. Step by step, I’m working toward turning Big If True into a non-profit news site, and I hope that many of us do the same. I know there’s a lot of work ahead for all of us, but we’re just crazy enough to do it.

Contact Mollie Bryant at 405-990-0988 or bryant@bigiftrue.org. Follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr.